#4: Security

The smart home standard Matter is intended to make IoT devices secure and protect them from privacy attacks. Two topics that often received little attention in the past – or made headlines right away. Who hasn’t heard reports about botnets that hackers used to gain access to a smart home via the Internet and take over devices? In most cases, these were poorly protected products with outdated software or standard passwords that offered little resistance to attackers.

For this reason, certain security requirements were already considered during the development of Matter. The standard is supposed to be “secure by design,” as it is called among experts. Its protective wall rests on three pillars: trusted devices, a secure control system and tap-proof communication. The basic prerequisite for all three is encryption.

A digital certificate for devices

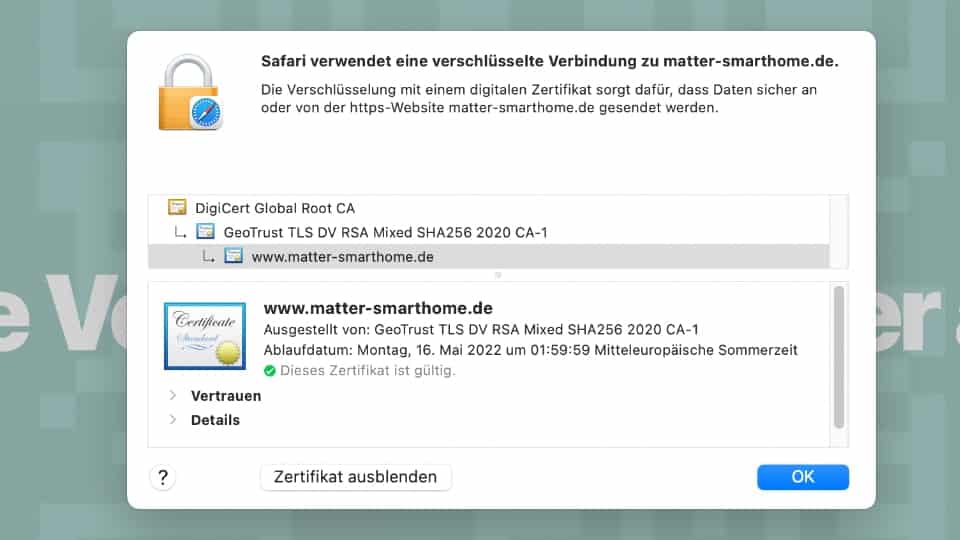

The principle is used millions of times on the Internet: Matter works with a PKI encryption process (PKI = Public Key Infrastructure), similar to a web server whose address starts with https://. While surfing, the browser checks whether the page visited has a valid certificate. This certificate – basically a dataset – must be issued by a trusted authority. Every browser contains lists of such trusted institutions. They are updated regularly and automatically as soon as one goes online.

If the certificate is in order, a tap-proof connection is established. The browser and server exchange a digital key (again, a data record) that only the two partners know. Strangers who have access to the connection could theoretically record the encrypted communication, but they would not be able to decipher the data because they do not have the necessary key.

According to all that is known so far, Matter will act in a very similar way: Every device sold has a unique certificate, the Device Attestation Certificate (DAC). It protects against counterfeiting and guarantees that the hardware really does come from the manufacturer on the packaging. Authenticity can be confirmed via a manufacturer’s certificate (Product Attestation Intermediate, or PAI), which in turn is signed by an official certification body, the Product Attestation Authority (PAA).

Key exchange during setup

During commissioning, these certificates play an important role. A new Matter device automatically sends out signals announcing itself after it is switched on. This can happen via Bluetooth, for example in the case of an LED lamp, or via a Zeroconfig protocol in the network (DNS-SD), as printers already use today to automatically announce themselves to a computer.

When the Matter controller – such as a smart speaker – receives this beacon, it prepares for connection. The so-called PASE process (Password Authenticated Session Establishment) begins, in which the controller and device already establish a secure connection. To accomplish this, they use a password that comes with the device – for example, as a QR code or combination of digits (see Benefit #3 – easy setup and “Matter is even more sophisticated than HomeKit”).

After the connection has been successfully established, the controller first checks the device certificate (DAC). If it is valid, the commissioner establishes contact with the smart home network. The new addition also joins an existing Thread network or WLAN in the process, if necessary. At the same time, a new digital ID is generated and stored on the device: the Operational Certificate (OpCert). In a sense, the Matter controller assumes the role of a trusted authority and issues the certificate. The OpCert can be verified by an additional root certificate, which also lands on the freshly installed product. It identifies the new addition as a member of the Matter network. Devices with the same root certificate trust each other.

From now on, all communication is encrypted. The digital key for the OpCert certificate is also stored on the device – along with a list of permitted functions. This Access Control List (ACL) regulates which other participants are allowed to connect to the device – and what they are permitted to do. For example, a light switch may be able to switch lamps on and off. But it cannot perform administrative tasks such as resetting lamps or putting them into commissioning mode.

All these measures are intended to prevent unauthorized persons from penetrating the network, intercepting commands or planting “hostile” products in the smart home that compromise security from within. Since every communication between the devices is authenticated and encrypted, hackers will ideally find no points of attack at all. And if security gaps should subsequently become apparent, the standard provides for the possibility of software updates. In an urgent situation, certificates can also be declared invalid. Matter controllers could react to this, for example, with an error message – similar to browsers that warn of a potentially insecure web server with an expired certificate.

The blockchain thing

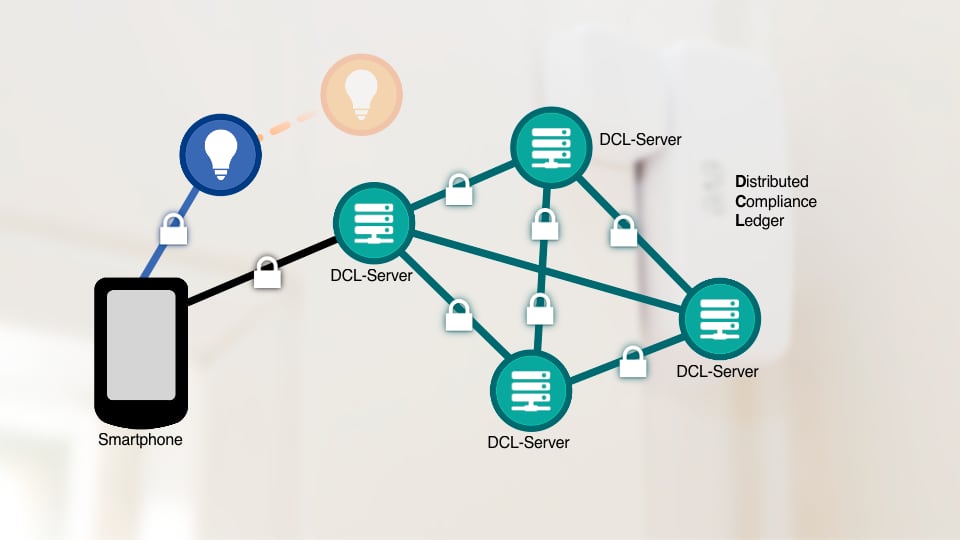

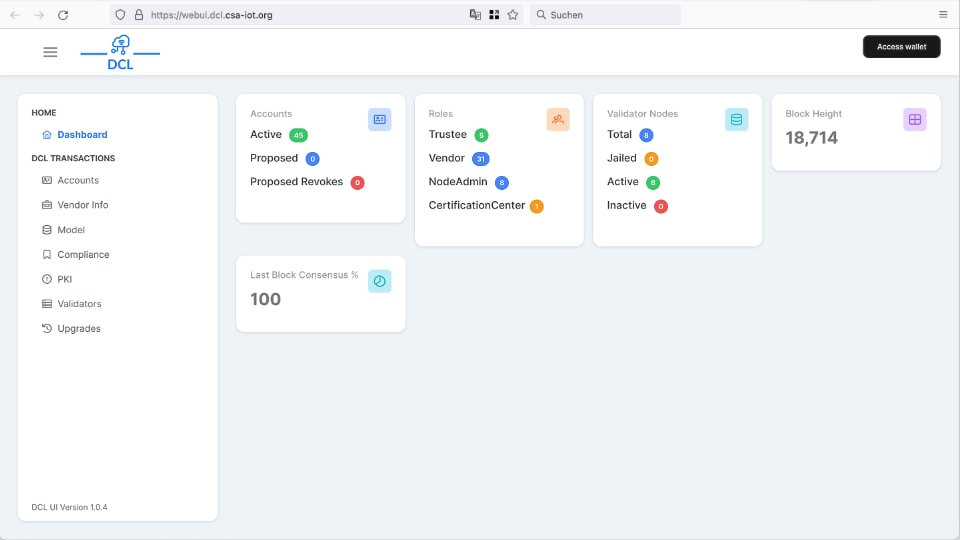

To enable the Matter installation to access safety-relevant information, the inventors of the standard came up with something. They gave it a digital register along with it. It’s called Distributed Compliance Ledger (DCL).

In this Ledger, various data are stored for each product – information about the supplier, such as the name of the company, brand, and Internet address. What device it is, its identification number, and whether it has passed the tests for conformity; a list of root certificates from the certification authorities (PAA, Product Attestation Authorities) and information on the current software version. This is because via the DCL, manufacturers can also provide firmware updates. The database then contains a link to the vendor’s server, where new software is available for download.

Technically, it is a network of independent servers operated by the Connectivitity Standards Allliance (CSA, link) and its partners. Each DCL server contains a copy of the database with all the information. The server themselves are connected to each other via a cryptographically secured protocol. Hence, the attribute “distributed” because there is no central account that could be attacked or easily manipulated.

The principle is similar to the distributed ledger technology in finance that underlies cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. It is generally known as “blockchain”. Companies that want to offer Matter products can set up such a DCL server themselves or use the services of the CSA.

And this is roughly how the whole thing works: The vendor writes the data for his product in the DCL directory. Once the device has successfully passed the certification process at a testing institute, the institute reports this progress to the CSA. The CSA then adds the status “certified” to the list. The Matter ecosystems – whether from Amazon, Apple, Google or another manufacturer – can now use the data to check if a device to be newly added is standards-compliant. Whether its device certificate (DAC) is correct and if new software is available for it.

The same game is repeated later in everyday life, for example when the manufacturer of a Matter product releases new software with enhanced functions. Data from the DCL network can then ensure that the download comes from the right source and that no one imposes a fake update on the devices that jeopardizes the security of the system.

To prevent misuse, the writing rights in the DCL database are restricted. For example, device vendors may only add their own products that are linked to their identification number (Vendor ID). Software updates must belong to the same vendor account to avoid being rejected. And only official CSA certification bodies can confirm or revoke device compliance. In contrast, read-only access is open to everybody.

In summary, Matter promises a high level of security – especially when it comes to communication between devices and the server infrastructure. IoT products in particular have often lacked this care in the past. What Matter ecosystems end up doing with their customer data is another story. It is up to them whether they collect and evaluate information with their own apps and cloud servers. After all, the business models of Amazon, Apple, Google, Samsung & Co. are not part of the standard.

Share this information: